Coronavirus contact tracing: what it is and how it works

During an infectious disease outbreak, one of the best tools available to public health experts is old-fashioned detective work: finding every sick person, then figuring out who they’ve recently interacted with. The technique, called contact tracing, helps bring disease outbreaks like COVID-19 under control.

In order to lift social distancing measures like school closures and “stay-at-home” orders, public health agencies will need to begin contact tracing aggressively and at a much higher level than just a few years ago. month.

This will prevent new virus cases from turning into new outbreaks. The United States can only relax stay-at-home orders and social distancing policies if it does enough contact tracing to detect new outbreaks before they explode.

Contact tracing is based on an obvious idea: people in close contact with someone who has COVID-19 are at risk of becoming ill. The process is not easy. When a person becomes ill, they are then interviewed by public health officials and asked who was exposed to it. Then they take that list and roll out to ask those people to either pay close attention to how they feel or self-quarantine. If a person who has been exposed is infected, their recent contacts will also be traced. The process continues until all that have been exposed are out of circulation. This stops the transmission of the virus.

“The viruses then have nowhere to go,” says John Swartzberg, clinical professor emeritus in the division of infectious diseases and vaccinology at the University of California, Berkeley’s School of Public Health.

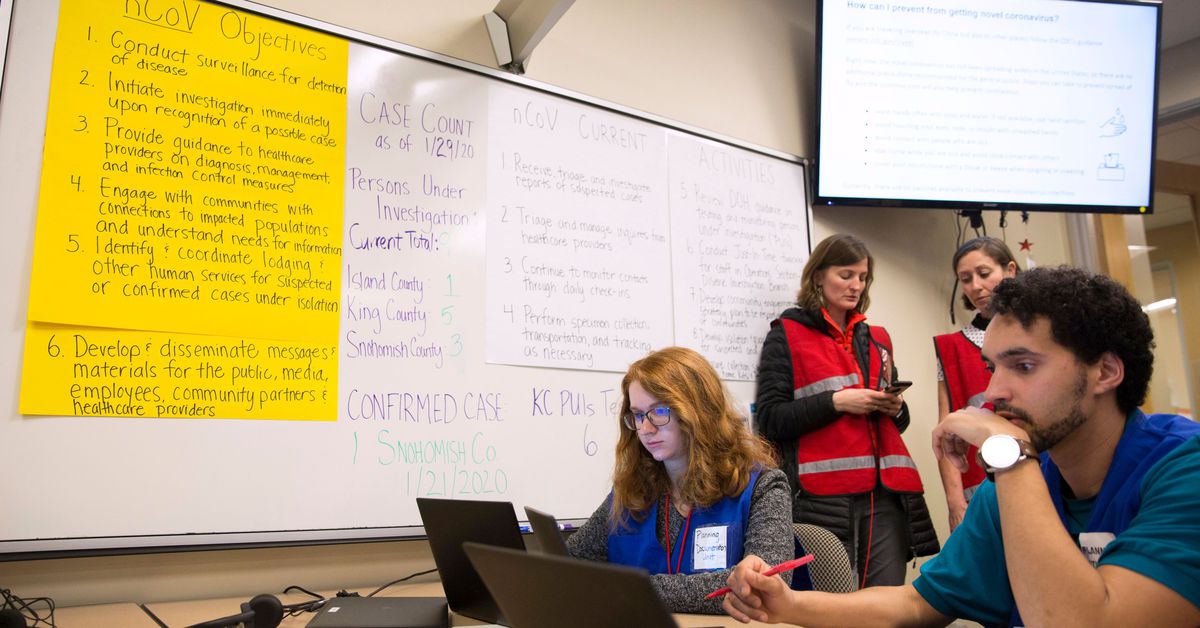

At the start of the coronavirus outbreak in the United States, public health officials carefully combed through the recent contact history of each newly diagnosed case of COVID-19. But as the number of cases began to climb in some areas, there were not enough resources to trace contacts for each new infection. A virus outbreak at a party in Westport, Connecticut, for example, left local disease experts with lists of hundreds of potential contacts — and they gave up trying to track them all down.

The United States initially failed in seeking contracts because we didn’t have enough resources to do what was needed, says Swartzberg. “We had to give up contact tracing pretty quickly,” but that doesn’t mean we can give it up forever. When the spread of the virus slows enough to make it possible to track cases, public health officials will have to backtrack to try to reduce the number of cases.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is increasing the number of people who can contact the trace nationwide, agency chief Robert Redfield told NPR. Ideally, that would be up to 100,000 new contact tracers, says Anita Cicero, deputy director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. The edge. These people need to be well-equipped — with apps or other technology — so they can be more effective.

The technology used by the US contact tracing strategy in the future may use cellphone data, for example. Today, Google and Apple announced that they are building a system to allow phones to use Bluetooth data to know when they are near each other. If someone tests positive for the virus, they could tell the app, which will then notify everyone whose phones were nearby.

The app could potentially fill a void in person-to-person contact tracing: you can only tell who has been exposed if you know who that person is. If you are diagnosed with COVID-19 and stood next to a stranger on the subway earlier that week, you will not be able to give that person’s name in an interview. The promise of Apple and Google’s effort is that it will also alert the stranger – if you and they have the app, of course. However, it’s still unclear how long a person has to spend with a sick person to become infected, so the app could alert many more strangers than they’re actually at risk.

Contact tracing also has ethical constraints: for example, only necessary information is collected and it is only used to protect public health. These ethical constraints should also apply to digital efforts to strengthen contact tracing.

“If a public health official knows where a person has been, if it’s public information, it’s no different,” said Lisa Lee, director of the Scholarly Integrity and Research Division. Research Compliance at Virginia Tech and former Executive Director of Presidential Bioethics for the Obama administration. Commission, says The edge. “It’s a lot easier to do it now, but that doesn’t make it any fairer or less fair.”

Justine Calma and Loren Grush contributed to this report.

Correction: An earlier version of this story incorrectly identified the Connecticut town with an outbreak.

Updated April 10, 3:30 p.m. ET: This report has been updated with expert comments.

Comments are closed.